By Bill Kovarik

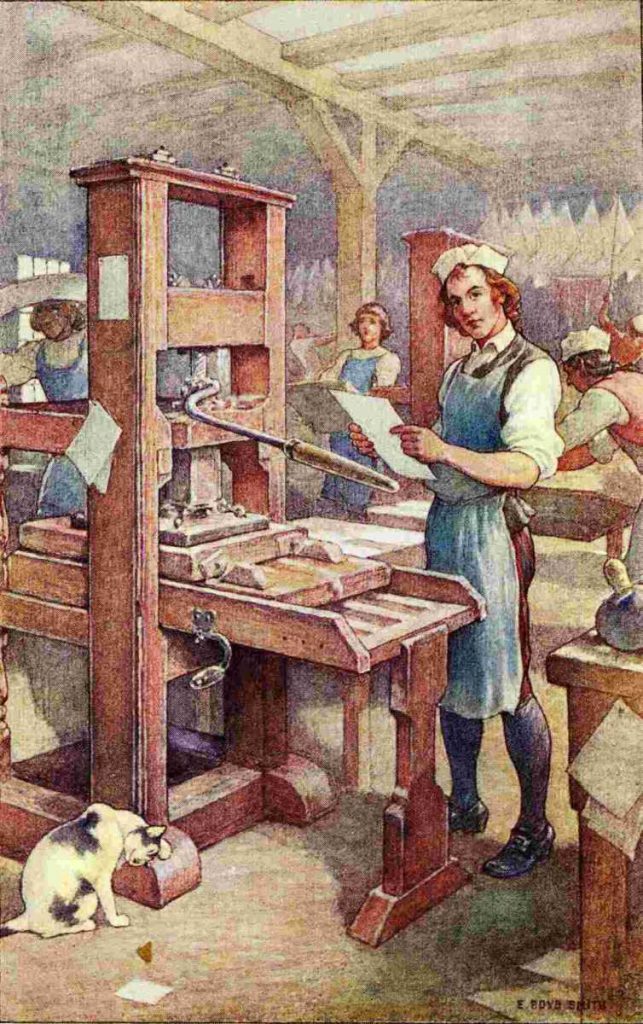

PRINTING CHAPEL, London, 1725. One man is setting type (left); another is pulling the press bar (also called the devil’s tail); and a third is preparing ink with two beaters (right). The young man pulling the press bar in this lithograph is Benjamin Franklin, who, as a journeyman, worked at John Watt’s London printing company in 1725. (Lithograph by Charles E. Mills, Public Domain, Library of Congress).

Imagine what it was like to work in a printing chapel from the 1400s to the mid-1800s, before printing and typesetting were mechanized. Imagine working alongside Benjamin Franklin or Horace Greeley or Frederick Douglass. As a printers devil (apprentice), your hours are long, the work is hard and the rules are strict. A 12 hour work day was not unusual, and you could be fined for whistling in the presence of a lady or leaving a candle unattended in the evening. Still, you’re glad to be here because it’s the most interesting place to work in the city. Printing is at the center of 18th century culture, and there is constant discussion about religion, government and all the great issues of the day. And it’s not all work. There are games like quadrats to play with the other devils. And at night, there are spooky stories about the spirits that were said to haunt printing chapels.

The light: The first thing you might notice is how the light fills the working areas of the printing company. In fact, one reason it is called a “chapel” is because of the large windows that allowed printers to see their work clearly. In that way they were like the scriptoria, where Medieval monks and nuns copied books by hand under large windows.

When you work at night, you have to follow strict rules about not leaving candles unattended. Seasonal light also plays a part in the life of a printing chapel. The big printer’s holiday of the year comes on Aug. 24, at the end of summer, when candles have to be used to work in the evenings.

The quiet: The next thing you might notice is that a printing company, like a monastic chapel, is a peaceful place to work. There are no motors or machines making noise — everything is powered by hand. Over in the corner, a printer might be reading out loud from the Bible, or Shakespeare, or novels like Robinson Crusoe. The entertainment helped keep everyone working steadily, and it was also part of the education for apprentices. Outside, noise of people in the market, and roosters in the back yards, and horse wagons on the cobblestones could also be heard.

The smell: Another thing you quickly notice is the unpleasant smell of grease and (there’s no way to say this politely) urine. The urine is kept in a vat out back, and it is used to tan the leather hides for the covers of the ink beaters. Its very important that the leather be tanned just right, because an imperfection in the ink beater will mean a flaw in the type on a page. One of the worst jobs you could have as an apprentice is to turn the hides over in the vats and stomp on them with your bare feet. (Of course you wash off at the water pump.) The white grease comes from rendered animal fat and is used to lubricate the carriageway and the handle on the presses. It also has an unpleasant smell.

So if you are an apprentice, you have to work with smelly things, and you also get dirty applying white grease and black ink to the presses. At the end of the day, you might look like a zebra and smell even worse. No wonder apprentices were called “printer’s devils.”

As an apprentice, you worked under a system of rules that were a lot like the other trades. You would start out as a printer’s devil (apprentice) by age 12, working in both typesetting and printing. You’d do this for seven years without pay (except for room and board). Then you move up to journeyman around age 18. At that point, you might be expected to go off traveling for two to three years and work for master printers in other cities. This would be called “auf der Walz sein,” which means “to be on the roll” in the German tradition. (The name for the dance called the waltz also comes from the same root word and idea.)

By the time you were a senior journeyman in your twenties, you would create a “masterpiece” as a way to demonstrate your talent. Eventually you would be considered a master printer yourself. If you were enterprising enough, it wouldn’t be that difficult to start your own printing business with a newspaper to publish on the side.

Both men and women worked in printing chapels. Women routinely worked alongside husbands, sons and brothers, setting type, selling books or stationery, and keeping the account ledgers. “A small group of women (numbering just under 20 before 1800) went a step further, becoming masters of offices and running the entire business for some amount of time,” according to an essay by Joseph Adelman. In most cases they became editors because their printer husbands died or because their sons were off fighting.

Both men and women worked in printing chapels. Women routinely worked alongside husbands, sons and brothers, setting type, selling books or stationery, and keeping the account ledgers. “A small group of women (numbering just under 20 before 1800) went a step further, becoming masters of offices and running the entire business for some amount of time,” according to an essay by Joseph Adelman. In most cases they became editors because their printer husbands died or because their sons were off fighting.

African Americans also worked in printing chapels, in the North as free men and as editors of abolitionist newspapers. The best known black printers were John Brown Russwurm and Samuel Cornish who worked on Freedom’s Journal,and Frederick Douglass, editor of the North Star.

Printers in the American South often used slave labor, but to do so was controversial even in that time. One editor, James Pleasants of Henrico (near Richmond), was kicked out of the Quaker church for using slaves in his printing company. State laws passed in the early 18th century made slave literacy a crime, and so fewer slaves could read, write, or set type in the years closest to the American Civil War.

After the Civil War, education was highly prized for African Americans and printing presses became one of the main centers of community. As a result, they were among the first Black institutions that were attacked in the “Reconstruction” Jim Crow era. Some of that long struggle is discussed in “Civil Rights and the Press” on this site.

Terminology of the printing craft

Like any technology, craft printing had its own technical words and traditions, and many are still found in everyday language. Common phrases — upper and lower case letters, or being out of sorts, or considering something by the same token, or minding your ps and qs — All these come from printing culture, as we’ll see going through the printing process.

There were also plenty of terms that have faded out over time, too. “Pull the devil’s tail” means to pull the press bar; “flying the brisket” is to work quickly with the frisket, a paper-holder on a wooden hand press; and being “on the stick” meant to be in a hurry.

Typesetting

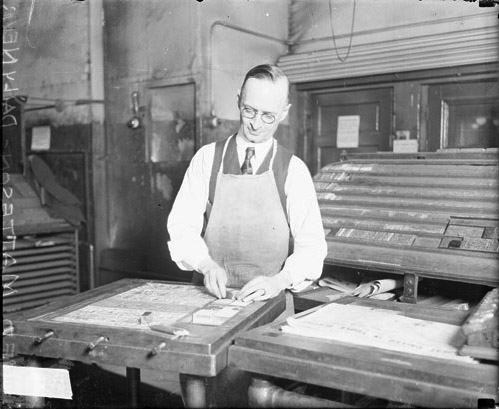

The first step in making any kind of newspaper or book would be to set the type. Typesetting had to be done by hand, letter by letter, until the adoption of mechanical typesetters in the early 20th century.

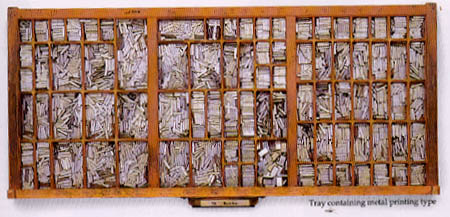

To set type, you would work in front of two cases with dozens of open compartments that held individual metal letters. The capital letters were in the upper case and the small letters would go into the lower case. Both of these terms — upper case and lower case — are still in use today.

To set type, you would work in front of two cases with dozens of open compartments that held individual metal letters. The capital letters were in the upper case and the small letters would go into the lower case. Both of these terms — upper case and lower case — are still in use today.

The cases had larger openings for commonly used letters, such as e, t, and a, and smaller openings for less commonly used letters like x, q and z. (Its interesting that when Samuel Morse was thinking about how to design telegraph code, he looked at type cases to see how often the different letters were used. “E”s were the most commonly used vowels, so he used one dot for an E. “T”s were the most commonly used consonants, so he used one dash for a T. )

One problem with hand set type is that it faces backwards in order to make it read forward in a mirror-image when it is printed. When setting type, you would pick it out of the case and place it into a long holder called a “stick.”

Let’s say you wanted to set the type for the phrase Life in a printing chapel. You would start with the letter “L” in the upper case, and place it on the right side of the line (not the left) in the stick. Then place lower case i, f, e, and a quadrat (space), and so on.

So you’d have this: .lepahc gnitnirp a ni efiL with the letters all facing backwards and upside down, too.

This can be confusing at first, and an apprentice typesetter might be told: “mind your ps and qs,” because a “p” would look like a “q” when it went in backwards. (Ps and Qs were also chalked up as pints and quarts by tavern keepers, and the double entendre for drinking and typesetting only reinforced the use of the phrase).

Usually, typesetters would work from instructions written in longhand on a paper held to the top of the composing case by a spike with a wooden handle (called a bodkin). That way it was easy to start setting type at the end of each line on the right side and work towards the beginning on the left. However, when an experienced writer / typesetter was in a hurry, they might set type while still thinking about what they were writing. This was called writing “on the stick.” Today being “on the stick” means that you are busy with a pressing task.

The first job you’d get as an apprentice would involve breaking up the columns of type after they had been used to print a book or newspaper. This is called “distributing” the type. You’d clean them off and sort the individual pieces of type back into the type cases according to letter, font and size. Apprentices would have to be sure that each piece of type went back into the right slot and that the cases were ready for the typesetters. If this cleaning and redistribution took too long, the typesetters might be “out of sorts.” In other words, they would not have the assortment of type of a particular font that they needed. Later, being “out of sorts” came to have a general meaning for a person who was feeling upset.

By the time you were a journeyman printer, you could probably set around 1,500 letters per hour, or about 20 words per minute. A column of type might take half the day – five or six hours — to set. Then an apprentice would spend another two hours distributing the type after the pages of a book or the day’s newspaper had been printed.

Proofing, Inking and printing

Once type was set, the lines of type from the stick would be assembled in long columns (galleys) on the composing stone. Then the type was inked and run through a small proofing press to find mistakes and make corrections. Once the corrections were made, all of the type would be assembled and then held together inside a frame. The frame would be locked down with little spacers called quoins and other wooden devices generally called “furniture.” (In a French printing chapel, you might say a mettre des pierres d’angle — put in the corner stones). Then the type would be placed on the bed of a press, ready to receive its coat of ink.

The ‘beater” (a skilled pressman or press woman) would carefully distribute ink in a thin, even layer on the surface of the type using two soft leather inking balls. If the ink was too thick it was said to be “fat,” and if too little, “thin.” Little smudges of ink on the page were called “monks.” Neither were acceptable, and the page had to be thrown out.

Once the ink was on the type, another pressman would place a dampened page of blank paper into a paper holder (called a frisket) and quickly fold it over the frame of inked type. (This is “flying the brisket.”) The final stage was to roll the type form down the carriageway. The pressman would pull on the long lever (or “pull the devil’s tail”), and the paper would be pushed into the inked type to get a crisp, evenly printed page. Then he would roll the type back, open up the frisket and hang up the page to dry.

A team of two pressmen and an apprentice could usually print a token of paper (250 – 258 pages) on one side each hour. A token was 258 sheets of paper, according to W. T. Brande & G. W. Cox Dict. Sci., Lit. & Art, or about half a ream. Today a “ream” of paper is 500 sheets.

The expression “by the same token” meant turning the sheets over once the ink has dried on one side in order to print on the other side of the pages. (Today it’s an expression that means you’re talking about similar ideas).

Once the pages were printed, they had to be assembled carefully to make a book. This involved placing, folding and trimming the pages in the right order and then sewing up the back of each “signature” (or quire or gathering) of pages, which would be from two pages to 16 or 24, depending on the size of the page and the kind of book being produced.

(You can try arranging a simple 8 page book signature by folding a piece of paper twice and then labeling each page with a page number and an arrow showing which way is up on the page. Now open the paper back up and you’ll see the numbers and arrows facing in different directions. The is the arrangement of pages you would use to print all eight pages on a single large piece of paper. It can get pretty complicated when it’s a 16 or 32 page signature, and many early printers manuals have long sections devoted to these signature arrangements).

Playing quadrats and getting a washing

The work could be tedious and exacting. To make the day go by more quickly, one printer might be asked to read aloud from works of literature or the Bible while others worked.

Most printing chapels had fairly strict social rules. Printers were not allowed to brag, or to whistle in the presence of a lady, or to leave candles burning if they left the room. Breaking any of those rules would result in a punishment, which was called a “solace,” and this could be anything from having to perform a nasty chore to putting money into the “ Wayzgoose” fund. The Wayzgoose was the printer’s holiday that took place every Aug. 24th

But printers had some fun too. A typical pass-time was a game called “quadrats” in Britain and “jeffing” in the US.

Quadrats are square blank type pieces used for spaces between typeset words. Like other pieces of type, each quadrat has a nick, or indentation, on one of its four sides. The game was described in a 1683 book on printing customs:

“They take five or seven Quadrats … and holding their Hand below the Surface of the Correcting Stone, shake them in their Hand, and toss them upon the Stone, and then count how many Nicks upwards each man throws in three times, or any other number of times agreed on: And he that throws most Wins the Bett of all the rest, and stand out free, till the rest have try’d who throws fewest Nicks upward in so many throws; for all the rest are free: and he pays the Bet.” (Moxon, 1683; Savage 1841).

But watch out ! If the sextant (manager) of the chapel caught you playing quadrats, he or she might have to decide on a solace.

Another view of Benjamin Franklin as a pressman at John Watts company in London, 1725. When he first started working there, he paid a five shilling “bien venu” initiation fee. He was transferred to the composing room, and the typesetters asked him to pay a second bien venu. When he resisted, the “Spirit of the Chapel” started “walking,” creating all kinds of private mischief. In the end, Franklin had to pay five more shillings — his second bien venu.

If you were in the habit of telling improbable tales, sometimes the other workers would express their disbelief by making loud banging noises on their presses or type cases. When every person in the room did it, the drumming could be deafening. This was called a “washing,” but any prank played on a new apprentice could also be called a “washing.”

If, for some reason, a pressman resisted a solace, and the workers in the chapel were determined to enforce it, then the Spirit of the Chapel was said to be walking in the shop. Whatever mischief is done to the pressman — such as mixing up his pages or getting his type “pied” (mixed up) — could then be blamed on the Spirit of the Chapel.

Benjamin Franklin described this problem in his autobiography:

I left Palmer’s to work at Watts’s, near Lincoln’s Inn Fields, a still greater printing-house. Here I continued all the rest of my stay in London. At my first admission into this printing-house I took to working at press [and paid the traditional initiation fee, called a bien venu] … Watts, after some weeks, desiring to have me in the composing-room, I left the pressmen; a new bien venu … being five shillings, was demanded of me by the compositors. I thought it an imposition, as I had paid below; the master thought so too, and forbade my paying it. I stood out two or three weeks, was accordingly considered as an excommunicate, and had so many little pieces of private mischief done me, by mixing my sorts, transposing my pages, breaking my matter, etc., etc., if I were ever so little out of the room, and all ascribed to the chapel ghost, which they said ever haunted those not regularly admitted, that, notwithstanding the master’s protection, I found myself oblig’d to comply and pay the money, convinc’d of the folly of being on ill terms with those one is to live with continually.

MORE

For more about tokens, reams, signatures and gatherings, start with the Oxford English Dictionary and then consider Joseph Moxon’s 1683 printing manual. You’ll find “tokens” to be either 250 or 258 sheets.